As I believe I've mentioned recently, there appears to be a growing tendency with respect to Canadian defamation law to stop treating everyone's "reputation" as necessarily sacrosanct, and to actually examine whether someone's reputation was truly damaged or injured before automatically assuming such damage and moving on to argue the typical defenses. More specifically, the discussion seems to focus on whether someone could have such a worthless, valueless reputation as a vile, rancid human being that there's little chance that that reputation could have been damaged any further.

Which brings us to Obergruppenführer Ezra Levant, of course.

In his 2016 defamation action against me (slated to go to trial, one guesses, in early 2027), Ezra claims to be terribly, terribly injured by my describing him as a "grifter", "huckster", "con man", "scam artist" and "bottom-dwelling, despicable sleazebucket and colostomy bag" (although I might be making that last one up); an obvious defense on my part would be, of course, to show that all of that is exactly his reputation, something I've been working on recently.

Here, for example, is where I believe I establish, beyond any reasonable doubt, that Ezra has a reputation as, specifically, a, "scumbag"; the evidence does seem overwhelming, does it not?

Moving on, it seemed worth pointing out how Ezra's reputation extended to being numerous variations of a "piece of shit," as you can read here (and remember, all these searches are fairly focused examinations of just Twitter).

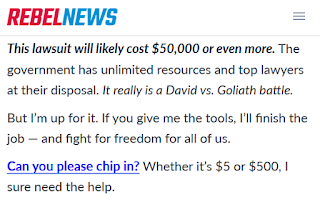

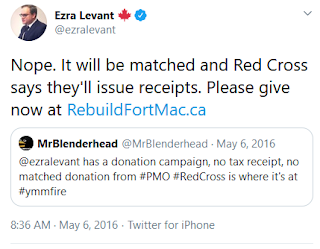

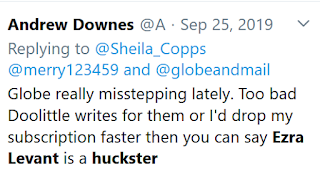

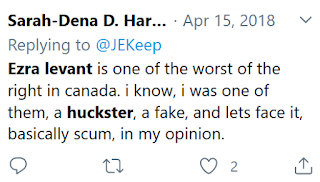

Slowing down only briefly to catch our breath, we soldier on to document Ezra's reputation as a "grifter" here, and a notorious scam artist here. So are we done? Well, not quite, as Ezra seems emotionally traumatized by being dismissed as a "huckster" and "con man" as well, so let's finish things off, and tie a big red bow around it.

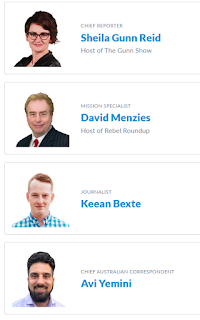

Once again, with a trivial Twitter search that even Sheila Gunn Reid could probably manage, we begin to establish Ezra's reputation as a huckster with this:

and this:

and this:

and this:

and this:

and this:

and wandering off from Twitter briefly, here's more from a 2017 piece from Now Toronto:

and on and on and tediously on it goes; I think I've made my point. Which brings us to Ezra's reputation as a "con man," which I will dispense with in short order as I feel I'm well into the area of massive overkill by now.

If you already have a solid and unshakeable reputation as grifter, scam artist and huckster, it's really not a leap to toss "con man" in there since, as any decent thesaurus will tell you, we're really into the area of synonyms by now, as this delightful example snagged randomly from Twitter demonstrates so nicely:

Put another way, if you already have a reputation as an idiot, an imbecile and a dumbass, being described as a "moron" really isn't going to move the needle a whole lot, know what I'm saying?In any event, I think I've made my point, and we'll be moving on to disembowel more arguments from both Ezra and his bloviating gasbag of a lawyer in short order. You won't want to miss that.

JUST TO PLAY IT SAFE, I can literally imagine Ezra and/or his lawyer, shrieking as to how, sure, Ezra may have an unshakeable reputation as a "con man" and "scam artist", but that doesn't cover any possible reference to him as a "con artist" ... no, seriously, it would not surprise me to hear that level of mouth-breathing dumbth from either of them so, let's deal with that, shall we, with this:

and this:and this:and this:and this:and this:and this:and ... but I fear I am becoming repetitive.Tune in tomorrow, when we imagine Ezra being outraged about being described as a "con huckster" or "scam grifter."